Although our ranch regeneration plan is multi-faceted, our primary grass and pasture regeneration tool is a livestock grazing technique we call Regenerative Grazing. This grazing method attempts to mimic, as closely as possible, the effects of a wild ruminant herd munching their way across a prairie.

Wild ruminants such as bison move in a tight mob to better ward off predators. On a wide open prairie with no fences to block their movements, they eat roughly 1/3 of the grass, trample 1/3 and leave 1/3 standing. The trampled third decomposes to enrich the soil. The third of the grass left behind quickly regenerates. They tend to eat whatever is in front of them because their movements left and right are limited by the mob. As they move, they distribute fertilizer and moisture in the forms of manure and urine evenly across the landscape. Subterranean life in the forms of earthworms, insects, fungi and bacteria thrive. Ruminants’ cloven hooves break up the soil surface, creating suitable conditions for germinating seeds. Both the bison and the prairie evolved to depend on this symbiotic relationship. The predominant grazing practices of modern ranching violates this symbiosis.

Continuous grazing is the most common livestock grazing practice in Central Texas today. In this grazing method, ranchers turn livestock loose in large pastures over extended periods. In the absence of predators, domesticated livestock have lost their mob grazing behavior. They wander freely throughout the pasture, favoring their preferred grasses, shade trees and the area around watering holes. As a result, the favorite grasses get eaten down to the root. Less desirable plants get left behind to over-propagate. Favored areas get compacted and over-grazed. Manure and urine are spread unevenly. Livestock trails develop, contributing to pasture erosion.

A slight improvement over continuous grazing is the practice of rotational grazing. In this grazing method, a rancher subdivides large pastures using cross fencing. The livestock are rotated between these smaller pastures every few weeks. Ideally the cattle are moved before they over-graze any particular pasture, but they can still over-graze spots within a pasture. The subdivided pastures have some time to recover between grazings, but most of the other characteristics of free-range wild ruminant grazing aren't achieved.

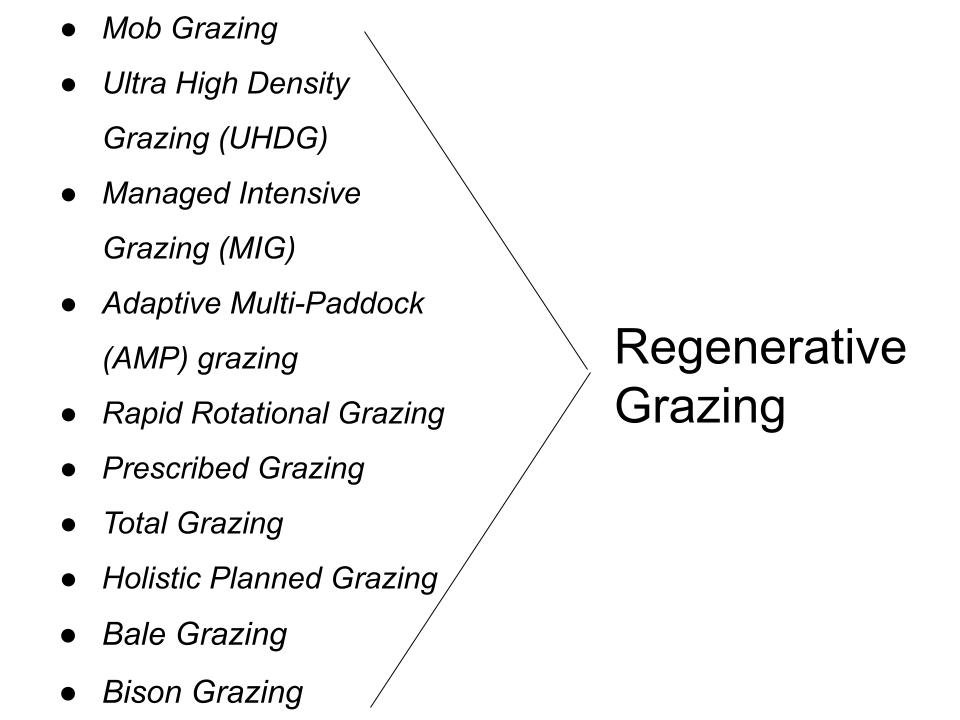

In recent years, many different grazing methodologies have been developed to counteract the negative aspects of continuous grazing. These methods go by names such as mob grazing, ultra high density grazing (UHDG), managed intensive grazing (MIG), adaptive multi-paddock (AMP) grazing, prescribed grazing, total grazing and holistic grazing. These techniques vary in subtle ways, but they all share a desire to return to the symbiotic benefits of wild ruminant herds foraging in tight formation across an open prairie or woodland savannah.

For our purposes, we're adapting all of the best practices from this collection of grazing techniques. We've chosen the umbrella term Regenerative Grazing to refer to all of them collectively. This descriptive term provides a mental model when we need to describe what we're doing and why we're doing it. Just picture a herd of bison moving slowly across a verdant prairie in tight mob formation and you'll have a pretty good idea of the what's and why's.

Although Regenerative Grazing harks back to ancient times, today's implementation is made possible by modern technologies. It wouldn't be possible without solar powered electric fencing, poly-wire, solar-powered water pumps and plastic water pipe.

To mimic bison grazing patterns as close as possible, we cross fence our pastures using permanent high-tensile electric fencing. We then fence off smaller temporary paddocks using portable electric poly-wire rolled off of a geared spool. We pump water to a portable trough in the paddock. We move the livestock to a new paddock on average once a day. When fully implemented, we will have 45 to 60 paddocks of 3 to 5 acres apiece, giving each paddock 6 to 8 weeks of rest on average between grazings.

The results we expect from Regenerative Grazing are as follows:

- Fewer parasite problems

- Parasite larvae in manure will hatch and die before livestock return to a paddock

- Fewer fly problems

- Cattle get a fresh paddock devoid of fresh manure every day

- Livestock will get a more varied diet of grass and forbs

- No more over-grazed pastures

- No more compacted and denuded spots in pastures where livestock congregate and less erosion caused by cattle trails

- Manure and urine spread more evenly across all pastures

- A layer of decaying thatch on the soil surface

- Aids in water retention

- Builds new soil as it decays

- Provides a substrate for growth of beneficial insects, earthworms, bacteria and fungi

- Faster recovery and regrowth of grass after each grazing

- Greater carrying capacity of the ranch in total since every inch of available land will be grazed uniformly

- Better management of both the livestock and the pastures since they’re being observed daily

- We can make real-time adaptive adjustments of paddock sizes and grazing periods based on our daily observations

- We’ll catch livestock health issues faster via daily observations

- Longer growing seasons for grasses and forbs since we keep them vegetative longer by clipping the plants before they seed out

- Creation of new top soil as thatch and manure decompose

- Improved soil health as the soil biome improves with beneficial worms, insects, bacteria and fungi

- Reduction of erosion in our pastures and creeks via improved ground cover, improved root systems and restricting livestock from sensitive areas

- Improved soil fertility

- Improved water retention

- Working off our beer guts because we have to get out and move cattle every day (not kidding).

Of course all these benefits aren’t achieved without costs. Some of these are the following:

- Labor required to move livestock on a daily basis

- Cost of electric fencing, chargers, batteries and solar panels

- Cost of pumps, batteries, water pipe, water storage tanks and solar panels

- Cost of additional stock ponds and/or water wells

- Cost of clearing brush to accomodate paddock fencing

- Maintenance costs for all of the above

These costs have to be weighed against the benefits.

The various grazing practices that we’ve lumped under the umbrella of Regenerative Grazing have both proponents and detractors. Anyone planning to pursue these practices should examine the arguments and evidence of both sides before taking the leap. We’ve provided a representative sampling of arguments on both sides in our Resources and References section. {Add link} An excellent literature review on regenerative grazing is provided at this link.

The main thing that strikes us as we research the relevant literature is the paucity of well-designed scientific studies of various grazing practices. Given the stakes, one would think that we’d know for sure whether and under what conditions these techniques work by now. That’s not the case. What we’ve found is a lot of poorly-designed studies built around the summer vacation schedules of undergraduate cheap labor comparing apples to oranges and the like. Along with that, we find a plethora of enthusiastic advocates providing anecdotal evidence that these practices work.

The one thing we do know is that continuous grazing is rapidly turning our family ranch into an eroded desert. Given that, we’re giving Regenerative Grazing a try. Can’t hurt.

Leave a Reply